Is a double chin truly fashionable? Does social media dictate our sense of beauty? How did Iran emerge as a world leader in nose jobs? In this article, we take you behind the scenes at ‘The Cult of Beauty,’ an exhibition at the Wellcome Collection in London, to explore the intricate history and impact of beauty aids. It’s a topic that has intrigued philosophers, mathematicians, scientists, and ordinary people for centuries, revealing that our present beauty standards have deep roots dating back to prehistoric times. These standards were evident in ancient rituals, such as the use of kohl in ancient Egypt for spiritual protection against the “evil eye.”

‘The Cult of Beauty’ offers a captivating journey through time, with over 200 objects, installations, and artworks, shedding light on how beauty has woven itself into the fabric of our lives across various cultures and eras. One striking example is the 18th-century ‘beauty patches,’ known as ‘mouches.’ These patches, originally used to conceal smallpox or syphilis scars, later evolved into elite fashion accessories, enhancing skin radiance and whiteness, even being adopted by sex workers to attract clientele.

Fast forward to the present, and we find that ‘spot stickers’ on beauty product aisles are reminiscent of these mouches, highlighting the remarkable continuity between past and present beauty practices. Jill Burke, a historian and professor, shares insights from her research, revealing that even in 1562, a book discussed how women could improve every aspect of their bodies, from head to toe. It provided guidance on achieving the ideal cheekbones and even how to create the coveted double chin, a highly desirable feature at the time. Women also sought makeup recipes to hide bruises caused by frequent beatings.

In the modern era, our lives have become entangled with beauty standards. Celebrities launch beauty brands with the same enthusiasm as they do for their films or records. Reality TV stars are the new beauty icons, often shaped by cosmetic procedures. Social media uses beauty algorithms to predict and digitally “rank” our appearances, even when we’re unaware of it.

The beauty industry’s growth in the past decade is no coincidence. In 2017, it was valued at $532 billion globally, and it’s expected to reach £662 billion by the end of this year. While this growth has brought benefits, such as a wider range of makeup options for diverse skin tones, it has also created casualties. Unrelenting modern beauty standards put immense pressure on individuals to maintain a youthful and filter-perfect appearance. Against this backdrop, ‘The Cult of Beauty’ exhibition becomes serendipitous, drawing attention to the industry’s vast economic potential and influence.

There’s a perceptible shift towards a “post-beauty” era in recent times. Celebrities like Ariana Grande and Bella Hadid have expressed regrets about cosmetic procedures, and research suggests a link between lip fillers and body dysmorphia, driven by exposure to unrealistic beauty standards on social media.

Pamela Anderson’s decision not to wear makeup at a recent Paris fashion week made headlines, and a study by the Mental Health Foundation revealed that over a third of UK adults feel anxious or depressed about their body image. It seems we’re finally realizing that amidst this beauty boom, we’re not always feeling better. Perhaps it’s time to question why.

Emma Dabiri, the author of ‘Disobedient Bodies: Reclaim Your Unruly Beauty,’ notes that the pressures to meet beauty standards are on the rise. Selfies and digital communication have given us an unprecedented level of scrutiny over our appearances, reducing us to two-dimensional avatars. During the pandemic, the phenomenon of “Zoom face” emerged as people stared at themselves on screens for prolonged periods, leading to a surge in cosmetic surgery and other procedures. Juno Calypso’s photography in the exhibition captures this self-examination, showcasing our quest for perfection through dystopian self-portraits.

Calypso’s collection of old beauty props, like the Linda Evans Facial Rejuvenating System, highlights how these devices often resemble horror and sci-fi props, emphasizing their surreal nature. The exhibition also delves into untold stories, such as makeup recipes rooted in Islamic medicine and the contributions of Jewish refugees expelled from Spain in the 1490s.

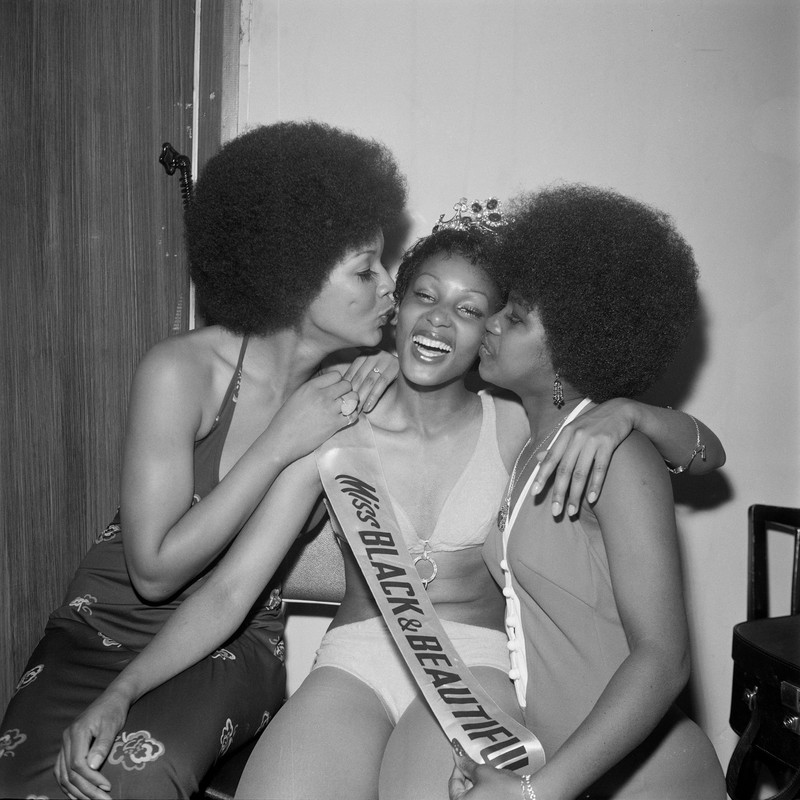

Other works within the exhibition explore Black queer visibility in British history, including the Permissible Beauty project, featuring portraits of Black queer Britons. These new portraits draw inspiration from 17th-century depictions of ladies celebrated for their elegance and appearance at the court of Charles II. The exhibition also features Shirin Fathi’s ‘The Disobedient Nose,’ which uses photography and sculpture to examine the beauty ideals imposed on women in Iran, a global leader in nose job procedures.

Throughout the ages, beauty has always offered moments of joy and sociability. Women in the Renaissance era, with limited education and freedom, expressed their identities and friendships through beauty rituals, such as having their eyebrows done together. Beauty also provided an underground economy for women who had been widowed or abandoned by their husbands, offering a safe space for enjoyment.

Many of the exhibition’s narratives center on our relationship with ourselves. As curator Janice Li shares, the timing of this exhibition is meaningful, coinciding with her personal decision to remove mirrors from her home. It led to a transformation in her self-acceptance and a compassionate approach to herself, regardless of society’s definitions of beauty.

In a world where beauty is a complex and ever-evolving concept, ‘The Cult of Beauty’ invites us to reflect on the past, confront the present, and envision a future where self-acceptance takes precedence.